The Whitetail buck—one that my compadres on both sides of the Rio Bravo would have called a “muy grande”—stood 50 steps away, staring at me. Under any other circumstances, I would have been shooting or already would have taken my shot. Unfortunately, my rifle was leaned against a fence post just out of reach. That’s where I had placed it before attempting to crawl over a five-strand barbed-wire fence.

I stared at the buck. He stared back watching me with great interest. The top wire was stretched tight. I had one foot on the left side of the fence and the other on the right. To say I was in a precarious position was an understatement.

What to do? Move ever so slowly in hopes the buck would continue staring at me? Or, make a daring quick move toward the rifle, knowing that in doing so, it’s likely I’d leave clothing and pieces of my hide and flesh (if not my manhood) on the wire’s sharp-pointed barbs.

Whatever I did would surely be a wrong move, I thought. Those mere seconds there seemed to transcend several lifetimes. I tried to come up with a solution that might provide me with a chance. I was hoping to finish stepping over the fence, grab my rifle, shoulder it and get off a killing shot. I hoped I might do all that before the old, massively antlered denizen of the Brush Country turned tail and disappeared into the myriad thorn and cactus bushes immediately behind him.

Thinking Back

For some reason, my mind drifted to a motel room in the border town of Eagle Pass. That’s where I met my long-time hero, mentor and later friend, John Wootters. We were preparing to conduct a helicopter game survey on the pastures that he and his friends had leased on the expansive Chittim Ranch.

After talking about the survey procedure, Mr. Wootters (someone I was in complete awe of) gave me a water glass full of Scotch whiskey. “You do drink Scotch…” he said then, more as a statement than a question. Even if I had no idea what Scotch was, I would have accepted the full glass he handed me. That first glass was followed by a second as I listened to my hero talk. Frankly, I am not certain what made me feel “higher” that day: the truly smooth single-malt Scotch whiskey that eased all pains, opened the mind and soothed the soul, or whether it was spending time listening to my hero’s greatly admired hunting tales. (I know it was the latter!)

John told stories about bucks he had hunted. I recall this one:

“I was near Laredo hunting an ancient ten-point buck. I spotted him from a great distance and decided to head in his direction hoping I could get close enough for a shot, or if I could not again find him, try to rattle him in. I cut the distance to within about 200 yards of where I suspected he was feeding. I started setting up to rattle. As I reached for my rattling horns, I spotted the buck staring at me less than 30 yards away. I was unsure what to do. The buck was heavy of beam, tall of tine, with deeply stained tarsal glands, definitely mature! He was one I really wanted!”

Wooters continued, “After a 10-second staring contest, I grabbed my hat and tossed it as high as I could. The buck watched my high soaring hat. I grabbed my rifle, found the buck centered in my scope and pulled the trigger. The buck fell dead before my hat hit the ground!”

And there I was in a similar quandary! If my hero and mentor could distract a buck this way, perhaps I could do it as well.

So, I slowly reached for my hat and sailed it high into the mid-December sky that was full of an approaching cold-front. The buck watched my hat, taking his eyes off me. I swung my leg over the fence and in one continuous move, grabbed the rifle, bolted in a round, found the buck in the scope with crosshairs settled on his on-side shoulder and pulled the trigger.

Then He Ran

At the shot, the buck wheeled on his heels and started to run for cover. Keeping an eye on the deer, I bolted another Hornady round into the barrel, found the departing deer in my scope and was about to pull the trigger when the buck collapsed mid-stride.

I kept my rifle trained on him until I was sure he would down. Before retrieving my western hat, (now nestled in the middle of a clump of sharp-spined prickly pear cactus), I walked to my buck. He was indeed an old one, with massive beams approaching six inches in circumference at the base and carrying excellent mass through beams and tines. Both beams supported three long points plus brows. They stretched a tape to 18 inches on the inside. A quick check of his teeth told me he was at least eight years old.

After retrieving my hat while standing at my buck’s side, I said out loud to no one, “Is this what would Wootters have done, and what would he say now?”

Actually I could hardly wait to get back to camp, and later into town, where I could find a pay phone (this was long before cell phones) to call John. I wanted to tell him what had happened and how he had helped me take a “muy grande.”

Through my association with John Wootters, who at the time wrote the tremendously popular monthly “Buck Sense” column for “Petersen’s Hunting” magazine, I learned much about Whitetail deer hunting and particularly about targeting mature bucks.

I remember Wootters saying, “There are bucks, and then there are mature bucks, which are totally different from those that have not yet reached maturity.” I knew he was right based on my personal hunting experience, and from what I saw on the ranches I managed for quality deer herds, which at the time, were numerous.

Beginning during the early and mid-1970s and continuing through today, there was and is much interest in producing and hunting quality bucks with bigger bodies and antlers, these older age bucks whose bodies and skeletal system are completely grown. Once they’ve attained that age level, any nutrition not required for body maintenance can be channeled into antler development.

Nurturing Interest

While many others would like to (and do) take credit for our ‘’modern-day interest” in Whitetail deer, I believe it was John Wootters who planted the seed and nurtured it through his writing about hunting mature deer.

About that same time another fellow Texan, Jerry Smith, began taking pictures of mature bucks on Texas’ famed King Ranch. Prior to Smith, most Whitetail photos that appeared in publications had been taken by Leonard Lee Rue, a truly talented photographer. However, he had photographed mostly immature bucks. This was because the areas where he photographed were heavily hunted. If bucks developed legal antlers, they were shot before they had the opportunity to mature.

For the first time ever, though, someone—John Wootters—wrote about the joys and challenges of hunting older-aged, mature bucks. At the same time, Jerry Smith provided photos of Whitetails that showed what bucks could look like if given the opportunity to mature and grow old. The trend was set!

This was about the same time Wootters wrote his classic, “Hunting Trophy Deer,” published in 1977 by Winchester Press. The book quickly became a runaway best-seller. His book appeared around the time I got to meet him and began to spend time with him.

The prior year prior in 1976, Murphy Ray and Al Brothers wrote and released their book, “Producing Quality Whitetails.” That soon became the “bible” for those interested in producing quality Whitetails as measured by antler and body size.

Both Murphy and Al were my good friends. I replaced Murphy as the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department’s technical assistance biologist, a job where I worked with landowners and hunters to establish quality deer management programs throughout southern Texas. During those immediate and in ensuing years, I also often got to share the stage with these Whitetail deer pioneers. I personally started doing Whitetail deer research in 1969.

Project Collaborations

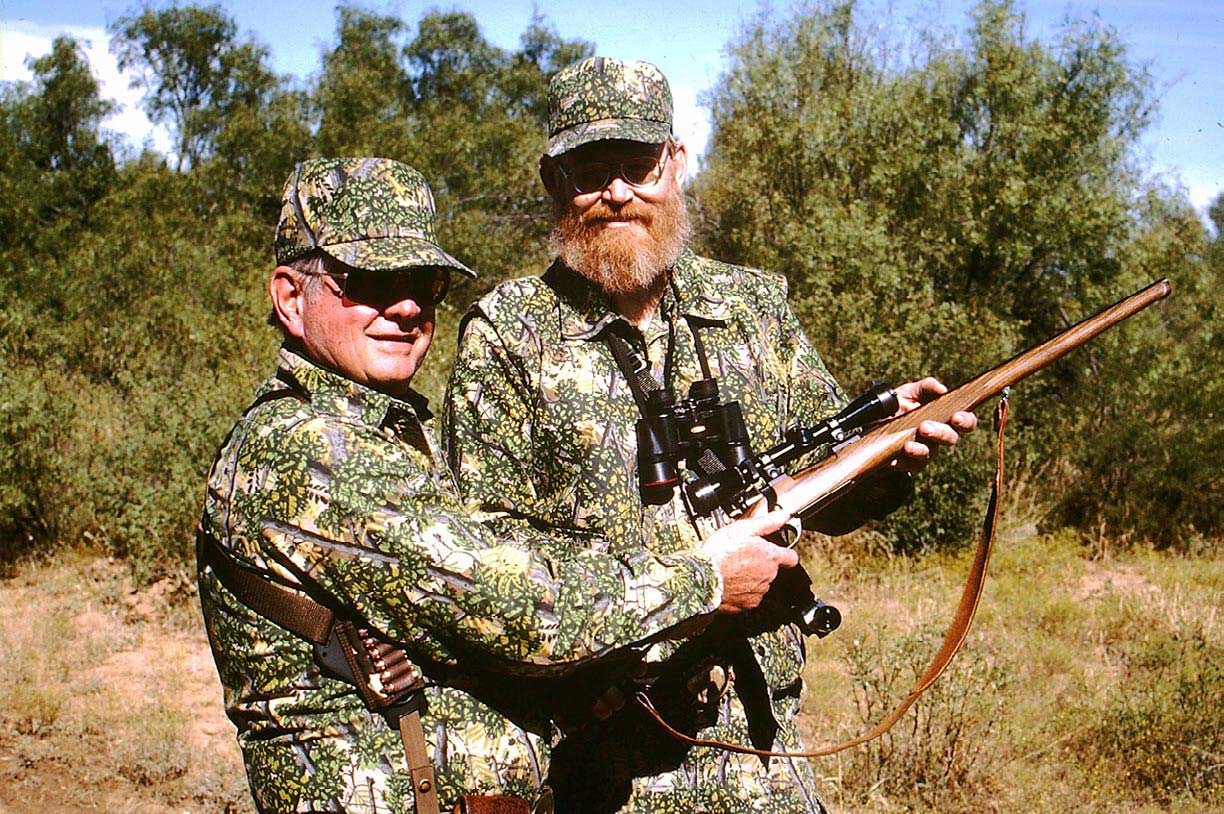

During the early 1980s, Wootters and I coordinated with Jerry Smith to produce a video, “Whitetails Judging Trophies,” in which we taught hunters and deer managers how to field- judge Whitetail antlers and how to age live deer.

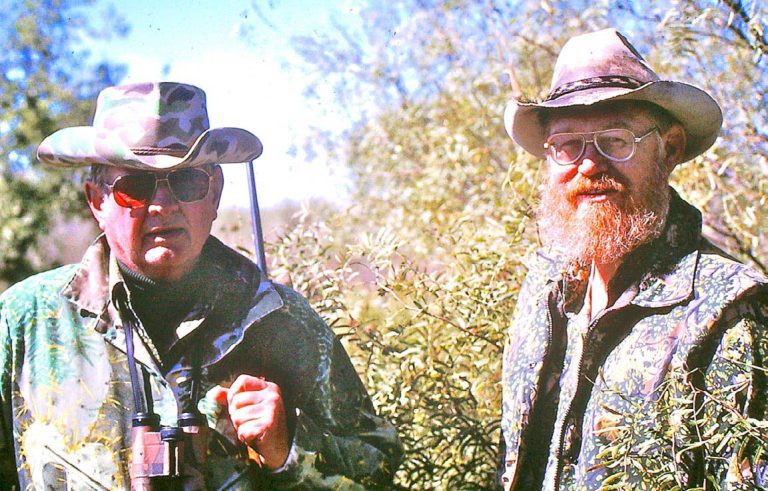

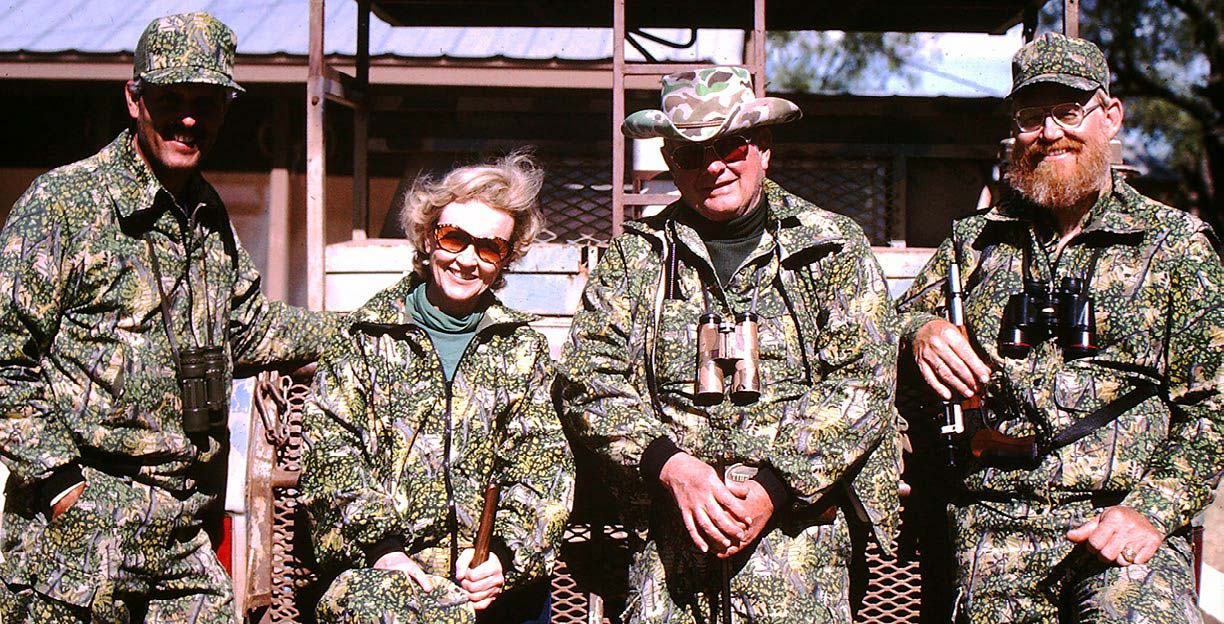

A few years later, Wootters and I, together with mutual friend Bill Bynum, were the featured speakers for the National Rifle Association’s Great American Hunters tour. We traveled together for weeks on end doing “deer hunting shows.” Throughout this process, I learned even more about my mentor and hero.

And Some Hunts

Thankfully too, there were times when we got to hunt together.

One such occasion we were hunting a ranch southwest of Carrizo Springs on the western edge of the South Texas Brush Country. It was a hunt set up through friends with whom I had often hunted, where I had taken some really nice South Texas bucks.

We had a tripod deer stand set up overlooking an expanse of low brush interspersed with dense stands of prickly pear cactus and a winding dry creek. It was an area that, once the local rut kicked in during mid-December, we often saw mature bucks. I planned the hunt so John Wootters would be there approaching the peak of the rut.

After his arrival at about 9 a.m. one day, I showed John where the stand was along with trails that lead into and through the area. We found several fresh scrapes, including one less than a hundred yards from the tripod. John stopped, turned his back, then said, “Excuse me for a moment.” Turning away, he urinated into the scrape. Moments later, he turned toward me with a sly smile and said, “Brings them back quicker, thinking a new buck has arrived on the scene.” He continued, “Within less than 30 seconds deer can only smell the ammonia and uric acid. Afterward they cannot distinguish deer urine from human urine.” I had heard the same thing from an old vaquero I often visited. He was someone who had taken many South Texas huge-antlered bucks and continued doing so all the years I knew him.

John asked to be taken back to the stand as soon as we returned to camp before the beginning of mid-day. He told us, “With this near-full moon, older mature bucks are moving mid-day. And I want to be in the stand before they return to freshen their scrapes. The buck whose scrape I freshened should be back before mid-afternoon.”

I dropped John off at the stand at about 10:30, then headed to another part of the expansive ranch. Walking and rattling that afternoon, I rattled in 17 bucks, including eight older, mature, impressively antlered bucks which I could have taken. I would have pulled the trigger on any one of them, had I not been hunting for a particularly tall, wide, long main-beamed eight-point that had been seen during the ranch’s annual helicopter game survey. Good thing I passed on those bucks! Later in the month, I did indeed take the big eight-point; he netted in the upper 160’s!

Legal shooting time ended 30-minutes after sundown. I waited until 40 minutes after sundown then drove to where John waited. He smiled as I pulled up. “Saw 28 bucks this afternoon, all ages and all sizes. One I really liked was a wide, typical 12-point. But I never could get a clear shot at him as he chased does through the mesquites. I’d like to come back here in the morning and spend the day. We’re one day closer to the full moon, so I suspect there will be much movement between the hours of 10 a.m. and 3 p.m.,” he told me.

I knew John to be an “information keeper.” He had long recorded deer sightings and circumstances surrounding them, as he had been doing that for the past many years. His statements regarding deer movement were based on thousands of observations.

As we headed to camp John reported, “That scrape I freshened…15 minutes after I crawled into the tripod, a huge-bodied buck strode directly toward the scrape and made certain to reclaim it. His antlers were over six inches at the base, and he carried that mass through his antler spread. He had eight-inch-long brow tines. His back tine was a foot long, and his next two points were 10 and eight inches long.” I caught that he had only addressed one antler. John continued, “Had he not broken off his main beam just past the brow on the other side, no doubt he would have been a candidate for the Boone & Crockett record book! And, had that beam not been broken, we’d be loading him into the back of your pickup now, instead of heading back to camp.”

Great Camp Tales

After supper, sitting around the mesquite-fueled campfire and serenaded by coyotes, Senor Wootters told tales of the great stags he had hunted, of hunting leopards in Africa with a .45-70 Ruger No. 1, and of hunting with his .308 Win Sako Mannlicher and a whole lot of other rounds he considered as adequate to good for hunting Whitetails. Our talk subsided merely two hours before it was again time to get up to go hunting.

That hunt and visit ended far too quickly. Thankfully, it was not the last time I hunted with John. On each of the ensuring hunts and every time we visited, I learned something about hunting big game species of all sizes and sorts, about guns, and of observations he had made while afield. He taught me how to tell truly fine Scotch whiskey opposed to merely drinkable whiskey and when to walk away from a conversation that was not going anywhere. That was helpful amid crowds we encountered when doing seminars and hunting shows.

Early on, I told my hero I that intended to become an outdoor writer to augment my wildlife management work and to help finance the hunting trips I hoped to make. John smiled and told me, “I wouldn’t recommend you do so…” He knew his response would only make me work all that much harder to become a writer and to continually strive to improve my craft. So, thank you, John!

I miss my mentor, hero and friend. John died in January 2013. But even today, every hunt I go on, every time I get ready to ascend a stage, I find myself wondering and asking, “What Would Wootters Do?”

Per our affiliate disclosure, we may earn revenue from the products available on this page. To learn more about how we test gear, click here.